Pat Thomas, Architecture, Abstraction

JazzFest Berlin 2025, Part 2

(This is the second of three posts on this year’s Jazz Fest Berlin. The first two are longer essays on particular sets by Wadada Leo Smith and Vijay Iyer and by Pat Thomas, the third a more general overview of the festival.)

I’ve seen Pat Thomas play numerous times over the years: first as a member of Oxford Improvisers, which Thomas co-founded, and then as part of the scene around Café Oto in London where, whether with Black Top, his evolving set of collaborations co-led with Orphy Robinson, with [ahmed], the phenomenally successful cooperative quartet devoted to reinterpreting the compositions of Ahmed Abdul-Malik, or in numerous other more ad-hoc combinations, on electronics or piano, he imports a distinct combination of instant authority and live-wire unpredictability to any context he appears in.1 His music widens and deepens all the time.

At the Festspiele Haus, audience members who’d protested at the loud points in the previous set by Amalie Dahl’s big band then walked out half way through Pat Thomas’s solo set. Their loss. It’s been excellent to see Thomas getting recognition of late outside the UK, of whose improv scene he has been so fundamental a part for so many years. Typical of Thomas that this high-profile festival appearance saw him dilute the music not one iota.

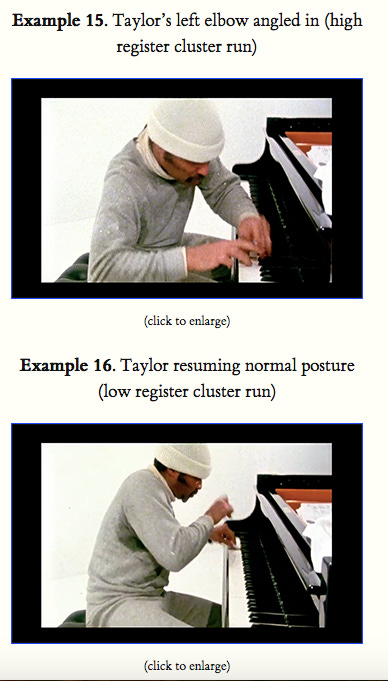

Thomas manifests absolute presence on stage: gregarious off it, on stage he is all business, sitting down and playing without the need of announcements or framing beyond the music itself. In an improvised solo set in the vein of the recent records The Solar Model of Ibn-Shatir and The Bliss of Bliss back to Nur in 1994, Thomas played what were essentially a series of short pieces: not quite miniatures, but relatively brief, each a study in a particular technique or texture. (One might call them études, perhaps.) Two were studies in rhythm and the harmonics that ring off a scraped or plucked piano strong, particular down the lower end of the instrument; the others focused on thick, splashy clusters and hand-over-hand runs dispensing with tonality as old news.

Thomas (‘Blind Tom’) Wiggins, to whom Thomas has previously paid tribute, was one of the first to use the tone cluster as device in a piano piece, in his programme-music depiction of the first large-scale battle of the American Civil War—a substantial Union defeat—The Battle of Manassas (1861). A cluster is a chord which exceeds the condition of a chord, a thick mass of adjacent notes. If a chord is like a familiar shape, a triangle say, a square or a circle, the cluster is like a shape, but one for which we do not have a name: a cloud, a thing whose form appears to be without form. In its history, the cluster is both representational and something which exceeds representation. Sometimes the cluster was the product of multiple intersecting lines, the excess of polyphony, as in some instances from Bach—a fleeting effect, where the layering of lines which must be heard as separate and individual for their effect briefly blurs. For Jean-Féry Rebel it stood for the primal chaos from wich God created the world; for Heinrich Biber, the chaos of the Thirty Years War which killed half the German population and decimated much of western Europe. Wiggins takes this up in his Battle of Manassas, where alternations of the anthems of respective parties—Dixie, the Union anthem, and La Marseillase played by rescuing forces on a train, are punctuated by sound effects including whistling and puffing to represent the train, left-hand grace notes that imitate drum rolls, and clusters representing cannon fire. Different kinds of freedom are heard in contestation. For Wiggins, the cluster pushes at the border of representation—the sound of cannon- or rifle-fire, the piano itself as mechanism, technology, machine. And first in Monk’s use of dissonantly-adjacent keyboard notes—not quite clusters, but moving in that direction—and then in Cecil Taylor’s of a variety of forms of clusters—explicated in Mark Micchelli’s excellent paper on Taylor’s piano technique—the cluster moves yet further in the direction of abstraction, as intricacy rather than simplicity, the thickness of texture overburdening the confines of the traditional chord, seeing how much information, how many notes can be pushed into the music to make it resonate and ring.2

In those forms of Black abstraction and, too, the anti-programmatic, anti-idiomatic form of abstraction of the UK and European free improvisation in which Thomas made his name, the cluster represents nothing so much as itself. It refuses to speak for or about anything, but its force, its pulverizing power, articulates presence, destabilisation, sound as mass rather than line, color-field rather than etching. And in its tendency to erase the traditional forms of harmonic or melodic linear or vertical movement, the use of cluster as method turns the piano into the orchestra of drums Taylor always said it was, tuned and pounding.

And abstraction too, might have to do with Islam, with Thomas’s Sufi faith—those qualities of attention, aesthetic or theological, that move beyond limits of representational form. (“Nur is an Arabic word meaning light, a very intense light that illuminates everything.”) Along with clusters, another way the music moves toward abstraction occurs in the way Thomas runs up and down more traditionally-formed chords: a way of thinking through different ways of organising sound than those of melody supported by harmony.

There’s an obscure track from Thelonious Monk’s final recording sessions in London