guitar

Dirar Kalash solo guitar set at Anagram Space, 15th February 2026

This piece comes from a manuscript-in-progress called Daybook. I’ll be posting more excerpts here at various points. The manuscript is currently conceived as a series of notes, conjectures, speculations, aphorism, fragments, spells; ways of thinking about what forms anti-fascist writing might take now. The writing is in-progress and subject to change.

The air quality has been so bad these past few weeks, someone says, because of the bombings in Kyiv. As the winds from Chernobyl blew over Berlin before: particles, smoke, debris blowing over, invisible by the time it appears but suffusing the air. History enters, not as an image, but just the simple fact of the air you breathe.

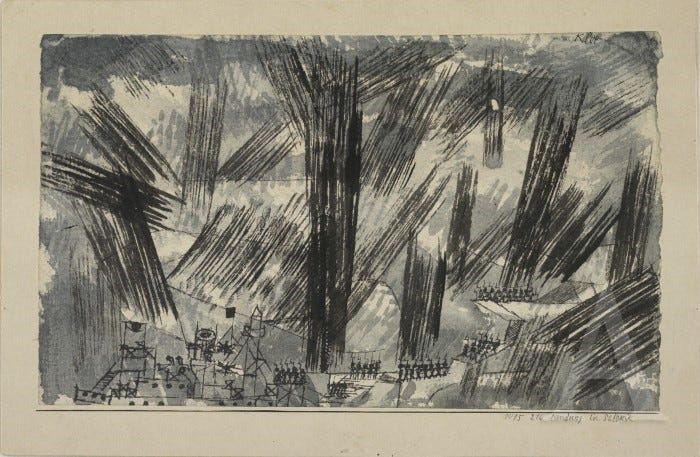

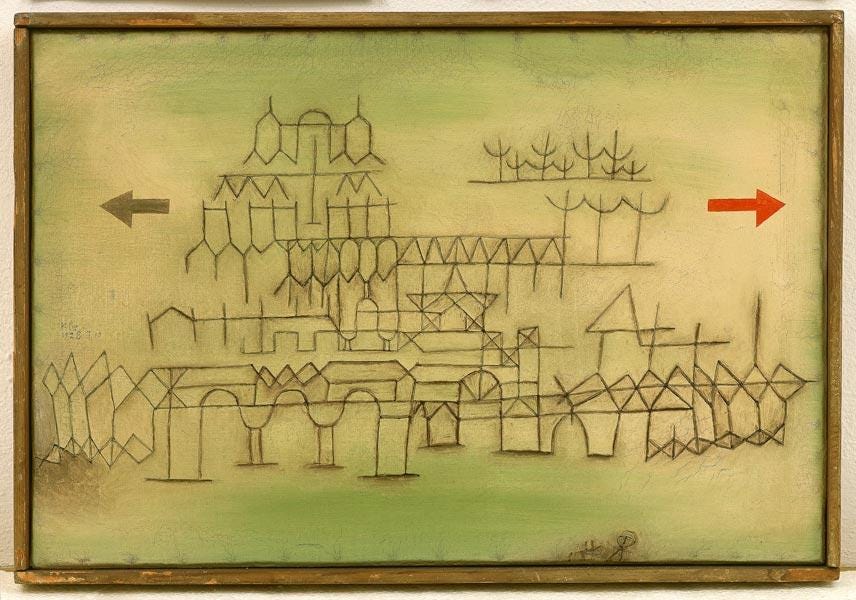

I go to a set in the record store late in the afternoon, on the border between day and dusk. A different kind of breathing, a different kind of air. Palestinian multi-instrumentalist Dirar Kalash plays a solo saxophone version of his piece, ‘We Can’t Breathe’, dedicated to George Floyd and Eric Garner and riffing off Fanon’s “combat breathing”. I heard him play this in a duo with bassist Luke Stewart late last year; he’s been playing versions of it for a decade or more, a morphing and ongoing registration of the situation, in Gaza, the West Bank, the US and elsewhere—a piece that doesn’t really have another end as those situations, too, deepen and worsen and lengthen. The names in the dedication stand in for all the other names, known and unknown, all the victims, the martyrs. In the piece, itself unlike the protest chants of “say [their] name[s]”, they have to resound silently, a linguistic core within the abstraction of an experimental music vocabulary that’s by now, at least in this context legible, even expected, but that still resists semantic extrapolation. A year or so ago, a friend talked about how, in the drawings Paul Klee produced during and after the first world war, you see reality—his reality, our reality, whatever split and shared landscape that term implies—“glitch”. Lines wandering off, matter out of place.

Following the November 18th Revolution, in April 1919, Klee become a member of the commissariat for painting in the Bavarian Soviet Republic. When it collapsed, destroyed by the military, he fled to Switzerland. What we see in those drawings at the turn of that decade are forms collapsing: but is what we see the new form of the soviet—prefigurative or existing, a utopian remodelling—or is it more negative—the collapse of the pre-existing world and then the collapse of the utopian experiment that seeks to replace and remould it? Somewhere between those two is the place we’re still in. The palace in passing. Oil and linen and cardboard, watercolour and ink. The briefest of moments before it sinks into the surface and dries. Inside that glitching, shuddering moment, frozen into representation or experienced as incoherence, silence, noise. The arrows point both ways.

Before he plays, Kalash speaks about the idea that politics, revolution, resistance is not ideology, or not just ideology, but something that is forced from one when one can no longer breathe, as Fanon says of anti-colonial revolt. Air through the lungs, rising up. The piece at once literalizes all that and turns it into representation: the deaths of racialized people in custody, in jail or on the street; DK speaks the words “I can’t breathe” into the saxophone before squalls of notes translate it or transcend or move through it, breath becomes sound becomes something else—not, he says, as a process of abstraction, or of abstraction as the removal of context, content, but abstraction as politics; or abstraction as the constant oscillation of the literal and the metaphorical, the capacity for translation in sound and speech of what it’s possible at a given moment to say amidst all the choking air.

Sound becomes something else, and that something else is not easy, it’s not nice, it’s messy or unpleasant, it’s what we’d rather gloss over, its sticky entanglements. Breath and the breathing apparatus, a trail of saliva from the saxophone, a trial, the phlegmy mucus matter of the lungs one coughs up, a habitual gargling or strangling vocabulary of vocalities, a matter of course. “Base materialism” and so on. Is how the spirit chokes to get out, is labour, bodily production, without which any notion of spirit and its entanglement with matter is just an empty mystical shell.

But the kernel is not necessarily rational.

“But a vision had to have been there.”*

The guitar set that follows is much longer, at least an hour, or so it seems. People shifting on their stools, and a phrase comes into my head, something along the lines of “free associating within our own conditions of unfreedom”. When DK starts the set, no one is quite sure it’s started, for at least a minute. Perhaps they think he’s warming up, testing the amp: one of those openings you get in smaller venues where people start without fanfare or announcements, matter-of-fact, that ambiguous transition. Recording her dreams and the thoughts of her brain as it shuts down for sleep, Christa Wolf writes something along the lines that it’s a tragedy that we can’t retain full consciousness of the very final moment before we fall asleep and are thus unable write it down. If we did, we wouldn’t be able to fall asleep: that’s sleep’s precondition. But somehow, perhaps precisely because she knows the impossibility of this transcription, Wolf maintains the desire to register that moment, that border: like the idea of the knowledge one’s meant to gain the very moment one dies, that split second—a wisdom about life one could transmit back to the living. And Wolf thinks