First Nettles, Earliest Persons

Books by Dom Hale and Jennifer Soong

In Amsterdam this August, it was a real privilege to have been hosted by Phil Baber and Elisabeth Rafstedt for the Don’t Pay Your Rent series at Elisabeth’s and Johanna Ehde’s Rietlanden Women’s Office, named for Bernadette Mayer’s ‘Walking Like a Robin’ in a nod to the city’s squatting history and an imagining of other possibilities, utopian but unsentimental. Published a decade ago, its relevance remains undimmed.

[…] each piece is anti-war and don't pay your rent, in fact remember: property is robbery, give everybody everything, other birds walk this way too

Birds walk and poems get, somehow made—through labour, even if unpaid: poems like Alix Chauvet’s, after Baudelaire, the contortions of their affect and syntax a fit for the jagged unfitting contours of this moment; Cleo Tsw’s, warmly biting, about surveillance, typography, Marx’s grave; and reconvening our panel from the Jazz Futures conference, Siyabonja Njica giving his first reading for a decade, reading poems by Vernon August and Gwendolyn Brooks and a short story from Dambudzo Marechera; and then, resonating in the space, not poems per se but poems in sound, Gabriel Bristow playing a ten-minute solo trumpet set which invoked Erroll Garner’s ‘Misty’ and, fitting the day of the week, Ellington’s ‘Come Sunday’. Gabriel’s duet recording with Steve Noble, out as a download release on Cafe Oto’s Otoroku, is great: I think this might have been the first time I’ve heard him play in person.

Gabriel has a propensity for half-valving that renders the authoritative, declamatory tone of his playing always sliding away—we’d talked about Nathaniel Mackey and the idea of ‘telling inarticulacy’ earlier at the conference: the false stumble, the performance of failure that tricks or dodges, fins another way to go on (around, to the side, disguised). There’s a dose of humour, too; some plunger-noted blarts or blasts somewhere between Bill Dixon and Bubber Miley. (How low does the note have to be before it can no longer be ‘blasted’ per se, the attack of the note swallowed inside itself?). There’s maybe something of Don Cherry’s thinness in the half-valving, and that juxtapository quality of atonal flurries as textural contrast to what is a primarily melodic, linear approach. But I should stop with the litany of names and influences. Gabriel knows the history of jazz, but it never feels like a forced parade of references. Afterwards, for example, when I asked about the half-valving, he mentioned, as a child, hearing the half-valved notes at the opening to the classic Lee Morgan solo on Art Blakey’s ‘Moanin’: those single moments from which a whole style emerges, microcosm and macrocosm. Style is first externally heard and learned, then absorbed and deployed as part of one’s own vocabulary—like the process of learning language, of imitation and internalization. At the same time, in jazz, perhaps more so than any other music, style is also a case of homage, display, reference, reverence. What matters, though, is that the music is its own thing, its own synthesis, what history sounds like in the present. Standing on the edge of the door to the packed room in the light-filled old school-house, the canal outside, the giant Free Palestine banner on the wall, one ear to Gabriel’s trumpet warming up, the other to the first readings, held in that moment, those two different kinds of music and language swarming together, other birds walking this way.

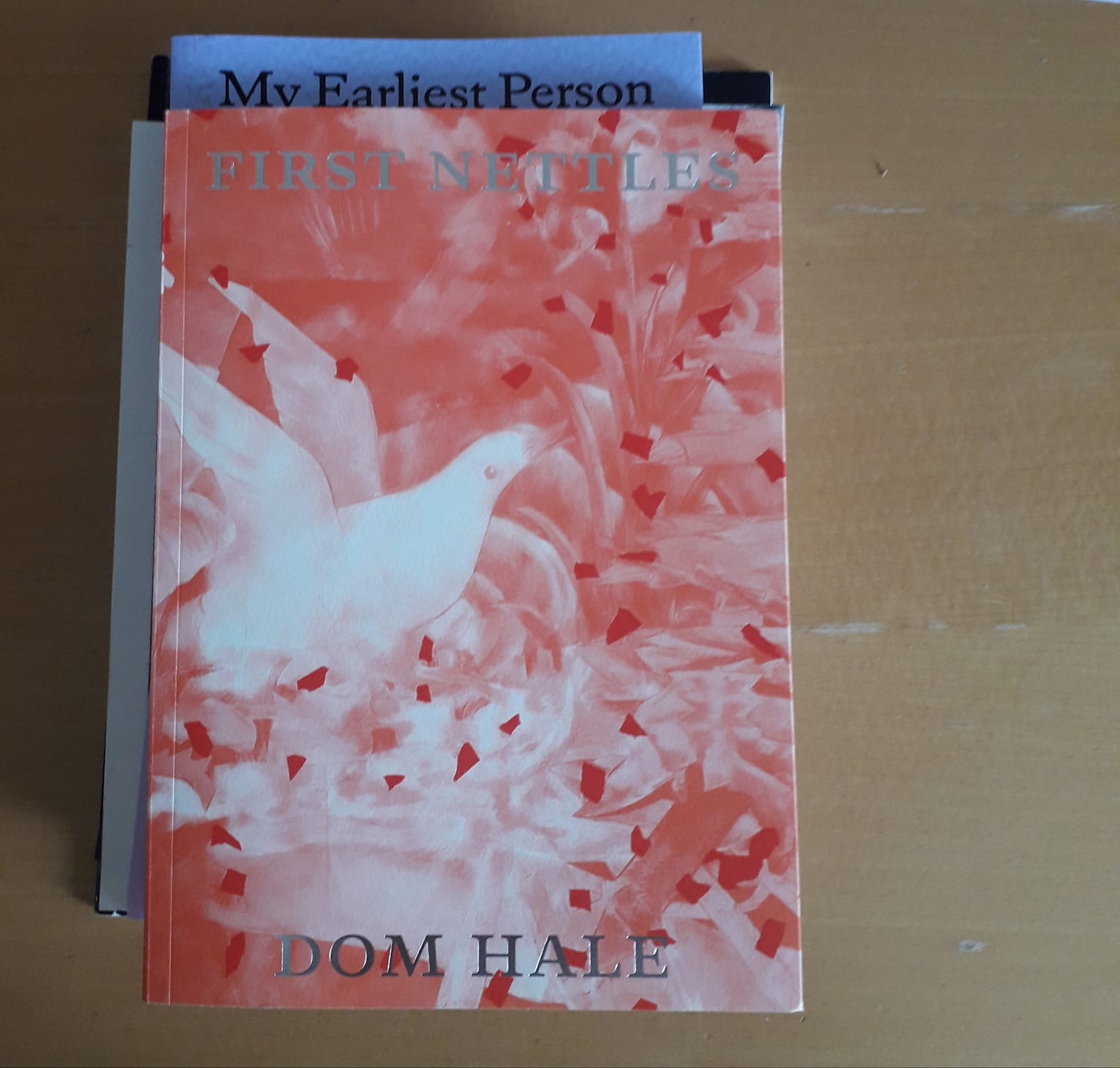

On my desk at the moment, the remainders of that trip, a pile of publications from Phil’s The Last Books, all as ever exquisitely made, designed, typeset, produced: the book not just as a medium for what’s inside—or the opposite, what’s inside an excuse to make a beautiful object—but the interrelation of all the elements—editing, typesetting, design—as an act of care. At the top of the pile, the two most recent books, by Dom Hale and Jennifer Soong, and in the pile too, a beautiful print from a student of Phil’s who’d scrawled the words from one of the poems from John Wieners’ Behind the State Capitol—soon to be republished!—direct onto the plate, hacking at the edge of the margin with dashes that smear into lines exceeding even the para-linguistic. Hale and Soong have both learned from Wieners in different ways—a few years back, Dom reviewed the most recent Wieners selected, Supplication, and, more recently, Jenn has written an excellent article on Wieners and the notion of the “minor poet”. Their two recent books—Hale’s First Nettles and Soong’s My Earliest Person—both collect poems from a period of several years.

Dom’s gathers much of the work written since his first book, Scammer, from the 87 Press in 2020: a book which inhabited the quick, satirical world of Kevin Davies’ The Golden Age of Paraphernalia or Stephen Rodefer’s Four Lectures—recently reissued in the NYRB series—meeting the internet-mediated discourse which is today reaching its full flowering head on, the world of Musk and Thiel furiously scanned and reacted to. As that discourse expands all the more, Dom’s work has moved away from that collision with the paraphernalia of what we’re maybe no longer calling “late capital”, more “late fascism”. Instead, he’s moved definitively into a lyric world he’s made his own—one which, as I mentioned birefly in a piece a few months ago on Dom’s and Tom Crompton’s pamphlet-poem-manifesto Mud Ramps—draws from Maggie O’Sullivan and Barry MacSweeney, their English from the North, its rich repertory of poetic or poeticizable words, their disjunctive take on the pastoral; their politics, too—amongst other things, the absolute opposition to that Thatcherism to whose early days they reacted and in whose long shadows we now live.

The book is in three parts, gathering together pieces published across the pages of magazines, some of the anonymous poems that open each issue of the Poets’ Hardship Fund magazine Ludd Gang. Besides Seizures, a sequence previously published as a pamphlet by Gong Farm in 2022, the poems are mostly discrete lyrics, ranging from one to several pages in length, and elaborately spread over the page. An eye which could find no surface where its power might sleep. Each poem feels like a gesture: a meditation, a gathering together, like going for a walk in language, in the light that precedes the clouds or the oncoming night. As the notes at